The Generative-Discriminative Fallacy

1. The Generative-Discriminative Dichotomy

It is customary to categorize predictive algorithms as either "generative" or "discriminative". Denoting by $Y$ the target and by $X$ the observable, discriminative algorithms are those that model the conditional distribution $P(Y|X;\theta)$ and generative algorithms are those that model the joint distribution $P(X,Y|\theta)$) (note that this entire discussion presumes a probabilistic perspective on predictive tasks).

Prima facie, the distinction seems senseless: the conditional distribution and the joint distribution are intimately related via Bayes theorem $P(Y|X)=\frac{P(X,Y)}{P(X)}=\frac{P(X|Y)P(Y)}{P(X)}$, and for prediction, $P(X)$ is in effect unnecessary since $\mathrm{argmax}_YP(Y|X_0)=\mathrm{argmax}_Y\frac {P(X_0,Y)}{P(X_0)}=\mathrm{argmax}_YP(X_0,Y)$.

Still, the situation is fundamentally asymmetric: many different joint distributions $P(X,Y)$ admit the same conditional distribution $P(Y|X)$. Hence common sense (and even better, Vapnik) suggests that discriminative models are preferable for prediction. After all, they model the problem directly, while generative models require solving "a more general problem as an intermediate step".

The conventional wisdom, however, is that there is a trade-off: discriminative algorithms tend to have a lower asymptotic error, but generative algorithms tend to converge a lot faster (see On discriminative vs. generative classifiers). Another piece of folklore says that discriminative models are more robust to violation of probabilistic assumptions.

This is somewhat true. For example, one may assume the generative model $X|y_i \sim \mathrm{Poisson}(\lambda_i)$ and $Y \sim \mathrm{Bernoulli}(p)$ and train it using MLE. If things go terribly wrong, and in reality $(X|Y=y_i) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_i,\Sigma)$, the classification algorithm will embarrassingly fail. On the other hand, under either of those assumptions, training the model discriminatively amounts to optimizing the appropriate loss of the objective $P(Y|X;\beta)=(1+\exp{(-\beta^TX)})^{-1}$. Had this have been done, the classification algorithm would have worked in both cases.

So it looks as if the distinction is not senseless after all.

Or is it?

2. Fallacies

The first misconception associated with the dichotomy, is about the imaginary “generative-discriminative pair”. This is an extremely misleading terminology. It seems to imply that a given model can be either “trained generatively” or “trained discriminatively”, and that it makes sense to directly compare the two approaches.

But that's wrong: generative-discriminative pairs typically consist of two completely different models. The procedure for making such pairs is something along these lines: start with $P_1(X,Y|\theta)$, derive $P_2(Y|X,\theta)$, and take as the generative counterpart the model $\hat{Y}_G=\mathrm{argmax}_YP_1(X,Y|X,\hat{\theta}_G)$ where $\hat{\theta}_G:=\mathrm{argmax}_\theta P_1(X_\text{train},Y_\text{train}|\theta)$, and as the discriminative counterpart the model $\hat{Y}_D=\mathrm{argmax}_YP_2(Y|X,\hat{\theta}_D)$ where $\hat{\theta}_D:=\mathrm{argmax}_\theta P_2(Y_\text{train}| X_\text{train},\theta)$.

Those are clearly two different probabilistic models, and the central point is this: if the assumptions underlying the generative model $P_1$ (which also underly $P_2$) actually hold, then $P_1$ is optimal, and will outperform any other model (including $P_2$). The statement "discriminative models have lower asymptotic error" is outright false in such generality. It's true only in a "distribution free" sense. Any advantage discriminative models may have, is due to misspecifications of the probabilistic models from which they were derived.

This brings me to the second misconception: robustness. The aforementioned paper discusses the family $\mathcal{H}$ of linear classifiers $\mathcal{X}\mapsto\mathcal{Y}$ where $\mathcal{X}=\{0,1\}^n$ and $\mathcal{Y}=\{\text{y}_0,\text{y}_1\}$, and concludes that reasonable generative-discriminative pairs ($h_G$, $h_D$) asymptotically satisfy $\epsilon(h_D)\le\epsilon(h_G)$ where $\epsilon(h):=P_\mathcal{D}(h(x)\neq y)$ is the generalization error with respect to the arbitrary distribution $\mathcal{D}$ over $\mathcal{X}\times\mathcal{Y}$. This is a trivial consequence of "modeling the problem directly".

Then it gives an explicit example: a naive Bayes classifier as a generative model, and a logistic regression as its discriminative adjoint. The derivation of this pair is simple: in the normal case, the naive Bayes assumption $P(\mathcal{X}|\mathcal{Y}=\text{y}_i) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_i,\Sigma)$ implies that $\ln{\frac{P(\mathcal{Y}=\text{y}_0|\mathcal{X})}{P(\mathcal{Y}=\text{y}_1| \mathcal{X})}}\propto(\sum\frac{(x_i-\mu_{i,\text{y}_1})^2}{2\sigma_i^2}-\sum\frac{ (x_i-\mu_{i,\text{y}_0})^2}{2\sigma_i^2})=\sum{\alpha_ix_i}+\beta$. Thus from the robustness point-of-view, estimating the coefficients $\alpha_i$ and $\beta$ by minimizing the classification error and using the resulting classifier instead of naive Bayes is a great idea, isn't it?

Well, sure. This would be a better distribution-free linear classifier. With an emphasis on linear. But if we’re already in the business of resilience under violation of assumptions, it worth noting that linearly is a huge assumption that could very well be wrong. And if this happens, it is likely that the generative naive Bayes would win big time.

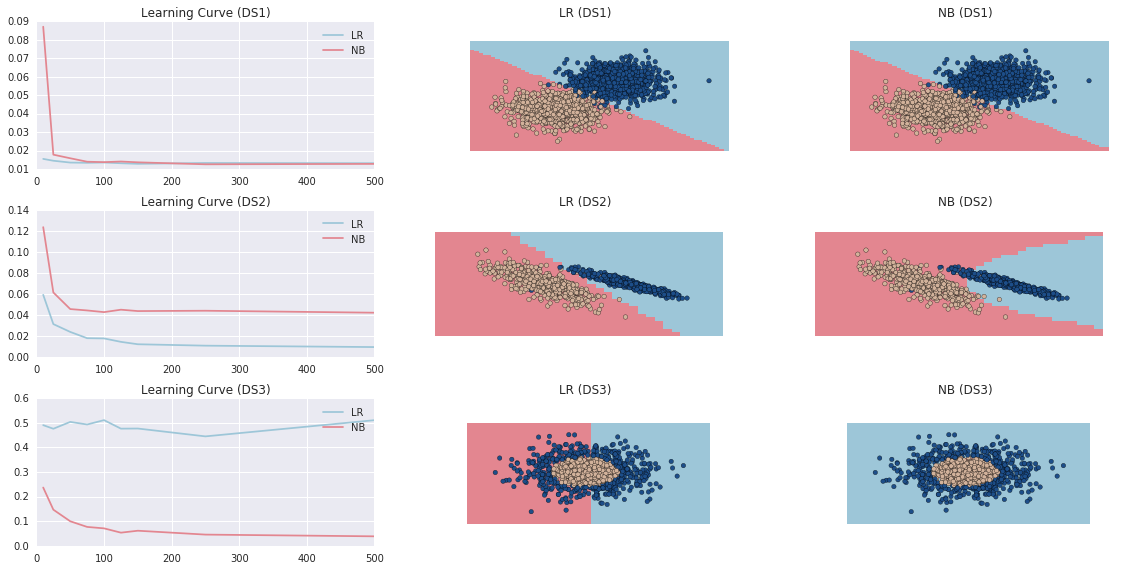

As a demonstration, here’s a comparison of a Gaussian naive Bayes classifier with a logistic classifier in 3 different cases:

- Linearly separable data (softly), distributed according to the model assumptions (NB should not lose).

- Linearly separable data (softly), distributed not according to the model assumptions (LR should win).

- Linearly inseparable data (NB should win again).

It should be emphasized that the failure of the logistic classifier above in the linearly inseparable setting, is not due to the fact that it's a "discriminative model". It fails because the derivation of the logistic training algorithm from the naive Bayes model, was crucially based on the assumption that the covariances of the distributions $P(\mathcal{X}|\mathcal{Y}=\text{y}_0)$ and $P(\mathcal{X}|\mathcal{Y}=\text{y}_1)$ are the same.

When this assumption is violated, the logarithm of the odds ratio is no longer a linear function of the observations. Instead all we can say is that $P(\mathcal{Y}=1|\mathcal{X})=\frac{1}{1+e^{-2F(\mathcal{X})}}$ where $F(\mathcal{X}) =\sum\frac{(x_i-\mu_{i,\text{y}_1})^2}{2\sigma_{i,\text{y}_1}^2}-\sum\frac{ (x_i-\mu_{i,\text{y}_0})^2}{2\sigma_{i,\text{y}_0}^2}$. This model can still be trained as a discriminative model! It's just no longer a logistic regression.

When comparing a regular generative naive Bayes model with such a proper "discriminative naive Bayes" (which is very much not equivalent to a logistic regression), the trade-off mentioned above indeed holds: the discriminative algorithm has a lower asymptotic error, while the generative algorithm converges faster to its asymptotic performance. But the situation is clearly subtle.

Finally, here’s a demonstration of a proper discriminative naive Bayes classifier. To train it, I simply used numerical optimization to minimize the cross-entropy of the quadratic function above. Warning: the following code is crude, and meant to be used only as a quick example (e.g. it employs an unconstrained optimization).

In [1]:

def predictor(mu1, sigma1, mu2, sigma2):

F = lambda X: 0.5*(np.sum(np.square((X-mu1)/sigma1), 1)-np.sum(np.square((X-mu2)/sigma2), 1))

return lambda X: np.clip(1.0/(1.0+np.exp(-2.0*F(X))), 1e-8, 1-(1e-8))

def objective(X, y):

res = np.zeros(len(y))

def func(mu1, sigma1, mu2, sigma2):

y_hat = predictor(mu1, sigma1, mu2, sigma2)(X)

res[y==0] = np.log(1-y_hat[y==0])

res[y==1] = np.log(y_hat[y==1])

return -np.mean(res)

return func

def p2vec(mu1, sigma1, mu2, sigma2):

return np.hstack((mu1, sigma1, mu2, sigma2))

def vec2p(vec):

n = len(vec)

return vec[:n/4], vec[n/4:n/2], vec[n/2:-n/4], vec[-n/4:]

X, y = sklearn.datasets.make_gaussian_quantiles(n_samples=200, n_classes=2, n_features=2)

X += np.random.normal(0.0, 0.1, size=X.shape)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = sklearn.cross_validation.train_test_split(X, y, train_size=0.7)

f = objective(X_train, y_train)

NBD = scipy.optimize.minimize(lambda vec: f(*vec2p(vec)),

p2vec(np.array((1, -1)), np.ones(2), np.array((-1, 1)), np.ones(2)), method='BFGS')

LR = sklearn.linear_model.LogisticRegression(fit_intercept=True)

LR.fit(X_train, y_train)

NBG = sklearn.naive_bayes.GaussianNB()

NBG.fit(X_train, y_train)

print 'Out-of-Sample Accuracy:'

print '\tDiscriminative Naive Bayes: ', np.sum(1*(predictor(*vec2p(NBD.x))(X_test)>0.5)==y_test)/(len(y_test)+0.0)

print '\tGenerative Naive Bayes: ', np.sum(NBG.predict(X_test)==y_test)/(len(y_test)+0.0)

print '\tLogistic Regression: ', np.sum(1*(LR.predict(X_test)>0.5)==y_test)/(len(y_test)+0.0)Out [1]:

Out-of-Sample Accuracy: Discriminative Naive Bayes: 0.983333333333 Generative Naive Bayes: 0.883333333333 Logistic Regression: 0.45

3. Dichotomy? Spectrum!

When it comes to the generative-discriminative dichotomy, the biggest fallacy of all is the dichotomy itself. Let’s see how it gets blurred until it completely fades away.

By now it’s clear that the choice between generative and discriminative algorithms involves delicate trade-offs. It would be wonderful to somehow integrate them in a way that combines their strengths.

Furthermore, in many settings unlabeled data is abundant, while labeled data is scarce. This is the case in semi-supervised learning and AI: it’s easy to obtain a huge collection of images, videos, texts or sound files. It’s much harder to manually encode their semantic content.

It’s sensible to hope that generative models would be able to extract structure from those mountains of unlabeled data (without any specific prediction problem to guide them), in a way that could be exploitable by discriminative algorithm designed for some specific tasks later (for which some modest collection of examples could be provided). This is a type of transfer learning.

That way or another, hybrid generative-discriminative models are strongly motivated by real-world problems - and over the years many papers, models, algorithms and software packages followed this path.

The first steps were very heuristic, and approached the matter by training the majority of the model’s parameters generatively (e.g. by maximizing the joint likelihood), and later train the remaining parameters discriminatively (e.g. by maximizing the conditional likelihood). Such models were shown to work better than both of their pure generative and pure discriminative analogues.

Continuing with the example above, let's fuse naive Bayes and logistic classifiers. Originally, I think such a model was first introduced in the context of text classification, where documents might have different regions with varying importance with respect to the classification task (e.g. a title, an abstract and a body). The method used, involved assigning each region an "importance weight" $\theta_j$ and modify accordingly the usual naive Bayes decision rule -

$$\sum_j{(\theta_j\sum{\ln(\hat{P}(X_i^j=x_i|Y=1))}})+\ln(\hat{P}(Y=1))\ge\sum_j {(\theta_j\sum{\ln(\hat{P}(X_i=x_i|Y=0))}})+\ln(\hat{P}(Y=0))$$

The estimations for $\hat{P}$ were obtained by training a separate (generative) naive Bayes on each region, and the weights $\vec{\theta}$ were discriminatively obtained by utilizing a jackknifeish "leave-one-out" strategy. Nicely, the model could be reformulated to look like a logistic-classifier: $\hat{P}(y=1|x)=\frac{1}{1+\exp({-(\alpha+\sum{\theta_j\beta_j})})}$ with $\alpha=\ln\frac{\hat{P}(y=1)}{\hat{P}(y=0)}$ and $\beta_j=\ln{\frac{\hat{P}(x_j|y=1)}{\hat{P}(x_j|y=0)}}$.

Let's pause and consider the interplay between generative and discriminative algorithms in this model: intuitively, each region is treated as if it were internally conditionally independent, where the signals from different regions could be non-neglectably dependent. Statistically, the Neyman–Pearson lemma offers an interpretation: each of the $\beta_j$'s values is a function of the significance given by a likelihood ratio test performed on a certain projection of the features-space. Then a logistic classifier is used as a meta-model that considers those dependent signals as competing indicators regarding the label.

Somewhat more general approaches (still heuristic) popped up later, and suggested “brute force fusion” in the form of a convex-combination of generative and discriminative models.

But actually, both type of models are really, rigorously, special cases of one unified form. As a motivation, consider the scenario above of pre-training a model generatively over unlabeled data, and only later tune it discriminatively.

Obviously, the discriminative likelihood $\mathcal{L}_D(\theta)=P(Y|X,\theta)$ requires access to target values. But so does the generative liklihood $\mathcal{L}_G(\theta)=P(X,Y|\theta)$. Going back to Bayes theorem (actually, just to the definition of conditional probability), we see that $P(X,Y|\theta)=P(Y|X,\theta)P(X|\theta)$. That's almost what we're looking for: a decomposition of the full model into a discriminative model and a separate generative model of the features space. All that is left is to emphasize the separation: $P(X,Y|\theta_1,\theta_2)=P(Y|X,\theta_1)P(X|\theta_2)$. This is indeed the required unified form.

It becomes clear from a Bayesian perspective. Write $P(X,Y,\theta_1,\theta_2)=P(\theta_1,\theta_2)P(Y|X,\theta_1)P(X|\theta_2)$, and note: the constrain $\theta_1=f(\theta_2)$ restores the generative model as a special case, and the constrain $P(\theta_1,\theta_2)=P(\theta_1)P(\theta_2)$ restores the discriminative model as a special case (since then $P(X,Y,\theta_1,\theta_2)=P(\theta_1)P(Y|X,\theta_1,\theta_2)$).

In between it's possible to interpolate the model freely and smoothly on the generative- discriminative spectrum (no longer a dichotomy). e.g. we may use $P(\theta_1,\theta_2)\propto P(\theta_1)P(\theta_2)\sigma^{-1}\exp{(-||\frac{ \Theta_2-\Theta_1}{\sigma}||^2)}$ and control the "generativity" of the model by modifying $\sigma$.

Training such models directly can be quite difficult. That’s another instance of a conclusion that comes up over and over again: working directly with probabilistic models is a questionable practice. But interestingly, this line of thought - of disputing the generative-discriminative dichotomy - leads to significant insights regarding some of the guiding principles of deep learning, and offers an explanation by means of boosting to the impressive generalization neural networks display.

As an appetizer, note how the hybrid-model from earlier has curious similarities to both max-pooling of feature detectors, and stacking. There’s much more to say about it, and I hope to write a sequel post soon.